Planning for the Vermont Estate Tax

Posted on Jul 03, 2012

Co-authored by Matthew D. Getty, Esq.

CAUTION: The Information Contained in This Article Applies to Estates of Vermont Residents (or Nonresidents Owning Vermont Property) Dying Before January 1, 2016. An Article Addressing the Vermont Estate Tax Applicable to Decedents Dying After 2015 Will Be Posted at a Future Time.

Background

It would be an understatement to say that estate planning to minimize potential federal and/or state estate tax liabilities has become considerably more complex in recent years. There are two principal reasons for this.

First, although we have seen a drop in the top estate/gift tax rate from 55% in 2001 to 35% today, and a dramatic increase in the amount of the federal estate/gift tax exemption—from $1 million in 2001 to $5,120,000[1] today—since 2009 we have faced the specter of a “sunset” of these increasingly favorable provisions and a return to the law as it stood in 2001. The law was originally scheduled to sunset after 2010, but it has now been extended to the end of 2012 as a result of a last-minute legislative compromise that was reached in December 2010.

Second, a number of states have made significant changes to their estate tax laws in recent years, principally as a result of the elimination of the federal estate tax credit for state death taxes paid. Prior to the elimination of the state death tax credit, nearly all states imposed an estate tax that corresponded to the amount of the credit allowed under federal law, and the exemption was the same for both federal and state estate tax purposes. In response to the change in federal law, a number of states, including Vermont, elected to impose estate taxes based upon the old state death tax credit, at the same time “de-coupling” their estate tax regimes from the federal exemption amount (by generally allowing a less generous exemption than that allowed under federal law).

The upshot of the changes in federal laws is that persons with assets in excess of $1 million continue to face the unpleasant prospect of having their estates exposed to federal estate taxes of 41%[2] or more if they fail to plan appropriately, without having the assurance that any expenditure of time and money to carry out such planning will not be rendered superfluous by subsequent actions of the Congress to maintain or increase the current exemption amount. Moreover, the looming lapse of the $5 million estate/gift tax exemption at the end of 2012 is driving many to plan on making substantial gifts this year. For married couples in this category, the planning is even more complicated.

As if the fluidity in federal transfer tax laws was not bad enough, taxpayers in “de-coupled” states such as Vermont face yet another level of complexity, made worse by the fact that there are significant ambiguities in the application of Vermont estate tax laws to many typically-drafted and existing estate plans.

The purpose of this article is to set forth some of the considerations in drafting a Vermont estate plan designed to minimize both federal and Vermont taxes in an extremely challenging and fluid legal environment.

Key Features of the Vermont Estate Tax

Vermont Estate Tax Rates & Exemption; Phase-out

Vermont imposes an estate tax on the transfer of the Vermont estates of decedents dying while resident in Vermont or who died owning Vermont situs property.[3] The Vermont estate tax return form and table of rates can be found here: http://www.state.vt.us/tax/formsincome.shtml . The tax rates range from .8% for estates of less than $90,000 to 16% for estates valued at more than $10,040,000.

Currently, Vermont law provides for a $2,750,000 exemption from estate tax.[4] However, it is very important to recognize that the exemption is determined in an indirect manner, by first calculating the Vermont estate tax liability on the entire taxable estate as if there were no exemption at all, and then comparing the result with a hypothetical federal estate tax liability, calculated by applying federal tax law as it existed in 2011[5] (with a 35% top rate), but using an exemption amount of $2,750,000.[6] The Vermont estate tax is the lesser of these two amounts.[7] For an estate valued at $2,750,000, there is no Vermont estate tax due because there would be no tax due under the hypothetical federal calculation, even though the Vermont estate tax calculation would reflect a liability of $165,280. As taxable estate values exceed $2,750,000, the hypothetical federal estate tax liability continues to be lower than the Vermont estate tax table amount until the size of the estate reaches approximately $3,400,000, at which point the Vermont tax table rates applied to the entire taxable estate will be lower than the federal liability, and will thus be used to determine the tax due in those cases.

The upshot is that estate assets in excess of $2,750,000 are taxed at a 35% effective marginal rate until the values exceed $3,400,000, at which point the progressive marginal rates of the Vermont estate tax table will apply to the entire taxable estate.

This “cliff” effect, whereby estates valued at or less than $2,750,000 are free from tax entirely, and estates valued at more than $2,750,000 but less than $3,400,000 are subject to a 35% marginal rate, creates substantial incentives for persons with estates in this category to employ planning techniques designed to avoid or reduce the impact of the Vermont estate tax. For individual estates over $3,400,000, there is no exemption available and therefore no “cliff,” although exposure to estate tax at marginal rates up to 16% obviously creates its own incentives for doing appropriate planning.

The exemption phase-out has particularly anomalous effects on the estates of married couples, as discussed under “Tax Planning Considerations for Vermont Residents” below.

No Vermont Gift Tax, but Taxable Gifts Reduce Exemption

Vermont does not impose a gift tax; lifetime transfers of assets are free from Vermont wealth transfer taxes. However, taxable gifts in excess of the federal annual exclusion amount (currently $13,000 per donee, per year) or other federal exclusions will reduce the Vermont exemption available at death. For example, the estate of a decedent who made prior taxable gifts of $1 million would be subject to Vermont estate taxes if the estate at death exceeded $1,750,000 in value, because the gifts will have used a portion of the decedent’s $2,750,000 exemption under the “hypothetical” federal estate tax calculation, thus increasing the estate tax amount calculated under that method (which would still be less than the calculation of the liability using the Vermont estate tax tables and would therefore be the amount of the Vermont estate tax due).

Uncertain Portability of Vermont Exemption for Married Couples

Federal law currently provides that a decedent’s estate may apply the unused exemption of a predeceased spouse against the decedent’s estate tax liability, provided that a timely federal estate tax return was filed for the predeceased spouse and a proper election was made on that return.[8] This rule will lapse at the end of 2012 unless Congress acts to extend it. It is unclear at present whether Vermont law provides for “portability” of the $2,750,000 exemption[9]. Because federal exemption portability is not guaranteed beyond 2012, most estate planners continue to use traditional “bypass” trust plans to maximize exemption utilization for married couples. These types of plans will be discussed below, in the context of the federal and Vermont tax considerations involved in drafting them. As explained above, once the “cliff” is reached ($3,400,000), the theoretical federal tax liability ceases to be relevant.

No Separate Vermont “QTIP”

Unlike a few states (e.g., Massachusetts), there is no provision in Vermont law or regulations for a separate, state level, “Qualified Terminable Interest Property” election; that is, a trust that fully utilizes the federal exemption cannot be partially QTIPed for Vermont purposes only in order to avoid the imposition of Vermont estate tax on the excess amount over the Vermont exemption while still getting the full benefit of the federal exemption for federal estate tax purposes.

Although it is not entirely clear at present, representatives of the Vermont Department of Taxes have stated informally that Vermont will recognize whole or partial QTIP elections for properly drafted trusts as long as the election is, or would be, binding for both federal and Vermont estate tax purposes. This matter is discussed in more detail below.

Tax Planning for Vermont Residents

Effect of the Vermont Estate Tax Exemption “Cliff” and Marginal Rates on “Typical” Estate Plans for Married Couples

Combined Estates with Assets Less than $2.75 Million[10]

Couples in this category, with estate plans that leave all their assets to each other (via joint tenancy, beneficiary designation, or will) do not currently have exposure to either federal or Vermont estate tax. On the other hand, couples with combined estates that bump against the $2.75 million “cliff” discussed above would be well-advised to consider the planning techniques discussed below, including gifting options, to avoid the 35% Vermont estate tax on the value of assets over the exemption amount (and below the $3.4 million ceiling) when the last spouse dies. As the examples below will demonstrate, gifting can be advantageous even though a tax may still be incurred. These couples should also seek professional advice annually to make sure that changes in the laws or in their financial situation do not require revising their plan.

Combined Estates with Assets Over $2.75 Million

Combined estates greater than $2.75 million are exposed to Vermont estate tax. The degree of exposure is a function of the size of the estate and the particular estate plan. Due to the variable impact of Vermont’s graduated rates, combined with the phase-out of the Vermont estate tax exemption, it would be impossible in the space here to discuss all of the possible outcomes of various plans, but the examples and illustrations below should serve to illuminate the considerations involved.

To begin with, let’s assume a couple has a combined estate of $5,040,000 (this number is chosen for simplicity in applying the Vermont tax table, and we will ignore the $60,000 deduction in arriving at the amount of the adjusted Vermont taxable estate). Let’s further assume that upon the death of the first spouse, the surviving spouse receives all of the assets outright. Because under federal and Vermont law there is no transfer tax imposed on gifts or bequests between married persons, no tax is imposed upon the first death. If we then suppose that the surviving spouse dies with an estate of $5,040,000, there is no Vermont exemption (having been phased-out at the $3,400,000 level) and the Vermont estate tax due is $402,800.

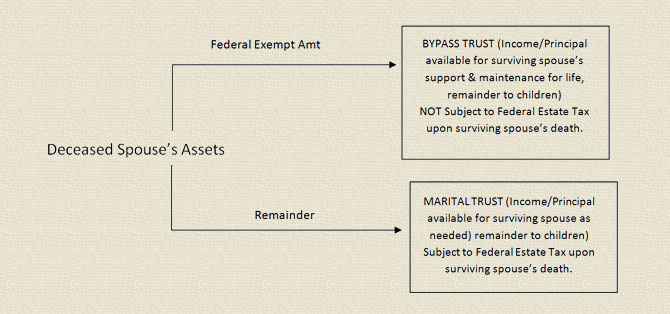

If this couple had executed a “typical” estate tax minimization plan several years ago, it would most likely look something like this upon the death of the first spouse:

In a “Bypass Trust Plan,” the assets of the first spouse are divided between two trusts, in such a way as to avoid payment of any estate tax, but so as to utilize the federal estate tax exemption of the decedent. Since it is usually not possible to predict the order of death, estate planners advise couples to divide ownership of their assets roughly equally, thus ensuring that each spouse’s exemption will be available to be utilized.

In this situation, if each spouse owned $2,520,000 worth of assets, upon the death of the first spouse the Bypass Trust would be funded with that amount, because it is less than the $5,000,000 federal exemption. Since there is a $2,750,000 Vermont estate tax exemption, there is no Vermont estate tax due upon the death of the first spouse. Additionally, if the surviving spouse does not own over $2,750,000 in assets upon their death, no Vermont or federal estate tax will be due at that time either. Thus, simply by having a “standard” estate plan in place, this couple would save over $400,000 in Vermont estate taxes.

Now, let’s change the facts a little and assume that this couple has assets of $7,080,000, with the same “standard” bypass trust estate plan, and that they have divided the ownership of assets so each has $3,540,000. As we have seen, upon each spouse’s death, their available federal exemption will be applied to their share of the assets, so no federal estate tax will be due upon the death of either spouse. However, because both estates exceed the $3,400,000 amount at which the Vermont estate tax exemption is phased out, each estate will be subject to Vermont estate tax of $238,800 ($477,600 total). Assuming the plan is written in a way so that the bypass trust is only funded with the Vermont exempt amount, that would leave $4,330,000 ($7,080,000 – 2,750,000) to be taxed in the surviving spouse’s estate (there would still be no federal estate tax, under current law), and the state tax would be $323,280, saving $154,320. Through this technique, the benefits of the Vermont exemption can be utilized for one spouse. For combined estates greater than $7,750,000, in the absence of federal estate tax exemption portability, the benefits of this technique are quickly outweighed by the federal estate tax cost of not fully utilizing both federal exemptions. As discussed below, a “Vermont QTIP” would be particularly useful in these situations.

Same-Sex Married Couples and the Vermont Estate Tax

For same-sex married couples in Vermont, considerations around maximizing the utilization of each spouse’s exemption are not a factor where federal estate taxes are concerned (due to the absence, at present, of a marital deduction at the federal level). It seems likely that currently many such couples simply leave all of the assets they own to each other, as with the couple in the first scenario described above. Since assets passing to a surviving same-sex spouse now qualify for the full estate tax marital deduction under Vermont law,[11] in the absence of a bypass trust plan, such couples could lose the tax benefit of one or both spouses’ Vermont estate tax exemptions, depending upon the size of their estate. Same-sex civil union or married couples living in Vermont with combined assets near or above $2.75 million should visit with a qualified estate planning professional to review their plans if they haven’t been reviewed since “de-coupling” occurred in 2009.

Trust Drafting and Funding Considerations

Importance of Splitting Estates

As illustrated above, in cases where the total value of a couple’s assets is not likely to be greater than $5,500,000, Vermont and federal estate taxes can be effectively minimized by using a “standard” bypass trust plan, so long as ownership of the assets is divided fairly equally between the two of them.

For combined estates in the $5,500,000 to $7,750,000 range, achieving the most optimal tax result requires “needle threading” between the Vermont and federal exemptions, taking into account federal exemption portability and the effect of Vermont’s marginal tax rates, as well as the exemption “cliff”. Each situation has to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, as will become apparent from the discussion which follows.

QTIP Trust Planning

The greatest planning difficulties at present spring from the unpredictability of the estate tax laws, the possibility of changes in the values of assets, and the difficulty in valuing some assets, which could all cause less than optimum federal and/or Vermont tax results from any particular bypass trust funding formula, depending upon the timing of deaths. In this environment, the ability of trustees and executors to determine the amount to fund into the bypass trust at the time of the death of the first spouse could be critical. For this reason, drafting the bypass trust so that it may qualify for a partial qualified terminable interest property (QTIP) election may be particularly helpful. A properly drafted QTIP trust will only qualify for the marital deduction to the extent the trustee or executor affirmatively elects (by claiming the marital deduction on the federal estate tax return), and the election may be made with respect to all or a portion of the trust assets.[12] In this way, a trustee could determine the amount of assets in the bypass trust that will utilize the decedent’s estate tax exemption based upon the facts known at that time.

Let’s look again at the example we discussed above, regarding the couple with assets of $7,080,000, who divided their assets equally, and who have a “standard” bypass trust plan. As we have already mentioned, when the first spouse dies, the “typical” funding formula would result in $3,540,000 of assets passing to the bypass trust, an amount that would be sheltered from federal estate tax under current law, but that would expose them to the Vermont estate tax in the first estate, and probably the second, as well. However, if the bypass trust were drafted so as to qualify for the QTIP election,[13] the trustee would have the option to elect to qualify $790,000 for the marital deduction, leaving $2,750,000 to be sheltered by the Vermont estate tax exemption and eliminating the potential Vermont estate tax. The decision would not be automatic. It would be necessary to perform an assessment of the potential for exposure to federal estate tax in the surviving spouse’s estate, including consideration of planning for charitable and non-charitable gifts that could reduce such exposure. There would also be income tax considerations, as discussed below. The analysis could be complex, and subject to many uncertainties, but it is likely that any assessment will be easier after the death of the first spouse than while both spouses are living.

As noted at the beginning of this article, there is no separate, Vermont level, QTIP election allowed under Vermont law; any such election that is made would have to be binding for both federal and Vermont estate tax purposes. Some questions concerning the viability of a “regular” QTIP election under Vermont law have arisen as a result of the fact that, with the significantly higher federal exemption, many estates subject to Vermont estate tax are not required to file federal estate tax returns. In those cases, Vermont estates are required to file a “pro forma” federal estate tax return (IRS Form 706), for the purpose of calculating the Vermont estate tax. Although Vermont law incorporates federal estate tax laws and rules (as they existed in 2011[14]) for the purpose of completing the pro-forma 706, some Vermont estate tax practitioners have expressed concern that such a “hypothetical” QTIP election may not be allowable under Vermont law. As noted above, officials at the Vermont Department of Taxes have stated informally that the Department will respect such elections made on pro-forma federal returns. Until that position becomes “official,” anyone intending to rely on a partial QTIP election would be well-advised to seek an advance ruling from the Department before making the election. [15]

Effect of Federal Exemption “Portability” or “Vermont QTIP” on “Bypass Trust” Funding Formulas for Vermont Estate Plans

As noted earlier, Federal law currently provides that a decedent’s estate may apply the unused exemption of a predeceased spouse against the decedent’s estate tax liability, provided that a timely federal estate tax return was filed for the predeceased spouse and a proper election was made on that return. Unfortunately, the provision is due to sunset at the end of 2012.[16] It is worth pointing out that in the event that exemption “portability” is made permanent at the federal level, funding formulas for bypass trusts could then be drafted to fund the maximum amount that would result in no Vermont estate tax liability, without running the risk of “wasting” the federal exemption of the first spouse to die. In many cases, the need to draft bypass trusts allowing partial QTIP elections would diminish considerably, although the income tax considerations we will be discussing next would still have an impact on the decision.

Similarly, if the Vermont legislature were to pass a law specifically allowing a separate “Vermont QTIP” election to be made with respect to assets in the bypass trust, the trust could be funded with assets up to the full value of the federal estate tax exemption without incurring Vermont estate tax upon the first spouse’s death, thus giving trustees more flexibility in planning to minimize the overall tax burden on both spouses’ estates.

Income Tax Considerations—Funding and Management of the Bypass Trust

As if the discontinuity between the federal and Vermont exemptions and tax rates doesn’t make planning complicated enough, there are income tax considerations as well. Take the following example.

James and Molly have $5 million in assets, which they have divided equally between themselves as part of the execution of a “standard” bypass trust estate plan tied to the amount of the federal exemption. At the time the plan was executed, their income tax basis in the assets was $1 million. Upon James’ death, under the funding formula the bypass trust is funded with his entire half of the assets: $2.5 million. No federal or Vermont estate tax is due at that time because the value of James’ assets is less than the federal and Vermont exempt amounts. All of James’ assets will have their tax bases adjusted to their fair market values as of the date of his death.

When Molly dies ten years later, all of Molly’s assets and the assets in the bypass trust have appreciated in value to $4 million each (by 60% overall). If all of the assets are sold upon Molly’s death, the tax scenario would look something like this:

VT Estate Tax Fed Estate Tax Fed/VT Income Taxes[17]

Bypass Trust -0- -0- $720,000

Molly’s Estate $286,640 -0- -0-[18]

Now, let’s look at what would have happened had James’ bypass trust been funded with $2 million,[19] appreciating to $3.2 million in the bypass trust and $4.8 million in Molly’s estate upon her death:

VT Estate Tax Fed Estate Tax Fed/VT Income Taxes “Savings”

Bypass Trust -0- -0- $528,000[20] $192,000

Molly’s Estate $375,920 -0- -0- -$89,280

Overall Savings: $102,720

As we can see, as long as Molly’s estate has sufficient exemption to avoid federal estate taxes, the cost of additional Vermont estate tax on Molly’s estate resulting from reducing the funding of the bypass trust is more than offset by the income tax savings achieved by the basis step-up at Molly’s death attributable to the additional assets.

A couple of observations should be made about this example. First, the benefits of this strategy disappear if the assets are not already substantially appreciated at the time of the first spouse’s death, due largely to the way the Vermont estate tax marginal rates apply and the fact that the estate tax is imposed on all of the assets, not merely the gain. Second, if federal estate tax exemption portability becomes permanent, and there is no need to use any of the exemption of the first spouse at the time of their death, even greater overall tax savings can be achieved in situations like this because more of the appreciated assets can be transferred to be taxed in the estate of the surviving spouse (and qualify for the basis step-up).

The problem for estate planners in these situations is, of course, the fact that it is not possible to know with any degree of certainty any of the following: (a) which spouse will die first; (b) whether there will be significant asset appreciation after the death of the first spouse; (c) whether there will be a change in estate tax exemptions and rates; and (d) whether there will be a change in capital gains tax rates. Despite all of this, a client may be willing to take those risks and pursue one or more of the following options:

- If the bypass trust has been properly drafted so as to qualify for a partial QTIP election, then as discussed above it should be possible under Vermont law to use the election to “dial down” the “bypass” amount to an appropriate level based upon the circumstances at that time, although as discussed, a certain amount of “crystal ball gazing” would still be required regarding future events leading up to the surviving spouse’s death.

- If circumstances change in the years subsequent to the first spouse’s death, the trustee could make discretionary distributions for the surviving spouse’s support out of the bypass trust first, rather than the “marital” share, or vice versa, depending upon the situation. Some trust agreements provide that the marital trust assets must be exhausted before distributions of principal can be made to the surviving spouse; estate planners who want to make this option available to trustees will need to omit such provisions.

- Some estate planners have suggested drafting trust agreements authorizing the trustee or a special trustee who is unrelated to the surviving spouse to give the surviving spouse a general power of appointment over all or a portion of the bypass trust, which could be exercised at a time the trustee determines appropriate. This would allow some or all of the assets in the bypass trust to qualify for the basis step-up at the surviving spouse’s death, at the expense of the exposure to federal and Vermont estate taxes. While including such a provision in trust agreements might at first appear to be a “no brainer,” there are reasons to be cautious about employing this technique. A trust agreement that gives the surviving spouse an interest for life, as a bypass trust does, necessarily has remaindermen who will take upon the surviving spouse’s death. Granting the surviving spouse a general power of appointment could result in disenfranchising some or all of the remainder beneficiaries. Although the trustee could seek the consent of the remaindermen to grant the general power, it may be difficult to obtain, particularly if achieving the ultimate tax benefits is uncertain. There is also the risk of a general power of appointment being imputed to the surviving spouse regardless of whether the trustee acts to grant the power, such as where the trustee is deemed to be “controlled” by the surviving spouse.

Gift Planning Techniques

Benefits of Making Lifetime Gifts

The benefits of making lifetime gifts are best analyzed by examining the separate impacts on gift planning of distinct features of the Vermont estate tax regime, while keeping in mind that in most cases some or all of these features may come into play simultaneously. This discussion assumes that outright gifts are made; however, the host of more sophisticated gifting techniques that have been developed for federal estate tax planning purposes could in most cases be employed with similar effects.

- Taxable gifts reduce the Vermont estate tax exemption that would otherwise be available at death.

As noted above, Vermont does not have a gift tax, but lifetime taxable gifts reduce any available Vermont estate tax exemption when calculating the alternative federal estate tax element of the Vermont estate tax after the donor dies. Example: Fred, a single individual, owns $5.5 million in assets. He makes a lifetime gift of $2,750,000 and subsequently dies with an estate of $2,750,000. The Vermont estate tax is $165,280, even though his estate was not more than the exemption amount.[21]

- All taxable gifts from estates above $3.4 million will avoid Vermont estate tax on the value of the assets that are transferred during life.

In the example above, if Fred had not made any gifts at all, the Vermont estate tax would have been $458,000, a difference of $292,720.

- For estates in the $2.75 - $3.4 million range, the size of the gift required to achieve a Vermont estate tax savings decreases as the estate size increases.

For an estate valued at $3.4 million, all but the smallest amount of gifts will result in a Vermont estate tax savings, since the hypothetical federal tax is $227,500, whereas the Vermont estate tax on the same size estate is $225,360. Any gifts made prior to death will reduce the size of the Vermont taxable estate, resulting in a computed Vermont estate tax that is lower than the hypothetical federal tax, which remains the same regardless of the amount of the gift (prior taxable gifts are added back for purposes of calculating the federal tax). For example, if a $400,000 gift is made prior to death, the Vermont estate tax on the $3 million estate at death is $187,280, while the hypothetical federal estate tax remains at $227,500.

On the other hand, an estate valued at $3 million would have to be reduced by more than $1,250,000 before the Vermont estate tax calculation result will be lower than the hypothetical federal estate tax liability of $87,500.

- The tax benefit of gifting is greater for estates that would be taxed at higher marginal rates, both because the assets themselves are not taxed and because the remaining taxable estate is taxed at lower marginal rates.

If Fred’s total assets had been $10,000,000, the “benefit” of making the $2,750,000 gift would have been $387,360, compared to $292,720.[22]

- Consider making non-taxable gifts to reduce the Vermont taxable estate while preserving the Vermont estate tax exemption.

Not all gifts made during lifetime reduce the Vermont estate tax exemption. Specifically, annual exclusion gifts, currently $13,000 per donee, per year,[23] will reduce the Vermont taxable estate at death without reducing the available Vermont exemption.[24] Similarly, direct payments for education tuition and medical care are excluded.[25] Example: Sally owns assets worth $3,000,000. Sally has five children and grandchildren. The oldest grandchild is enrolling in college; the annual tuition is $40,000. If she makes annual exclusion gifts to each of her descendants for three years, and pays for two years of the grandchild’s college education, she has virtually eliminated the exposure of her estate to the Vermont estate tax.[26] If no gifts are made, and her taxable estate is $3,000,000 at her death, the Vermont estate tax would be $112,500. If Sally’s assets appreciate in value between the date of the gift and the time of her death, the tax savings will be greater, although her remaining estate might increase into taxable territory again.

- Federal gift tax considerations—“window” of opportunity in 2012?

The federal gift tax exemption is currently $5 million. Unless Congress acts, the exemption will return to $1 million in 2013. Some estate planning advisors are recommending that people with estates over $1 million consider making gifts this year to take advantage of the current exemption. While it is not entirely clear that such gifts would escape some form of direct or indirect taxation should Congress fail to act, Vermont residents considering this strategy should be aware of the additional incentives under Vermont estate tax laws for making such gifts, as discussed above.

- “Deathbed” gifts.

Vermont currently has no “deathbed gift” rule; as long as the gift is completed before death, it should be excluded from the Vermont estate tax base, although there is no “case in point” on this question in Vermont.[27] Some states, such as Maine, have changed their laws to include in the estate tax base any gifts made within a year of death.[28]

Due to the requirement that gifts must be legally binding or “complete” in order to be considered to have removed the asset from the donor’s taxable estate,[29] it is advisable to plan for deathbed gifts as far in advance of death as possible. In many cases, the donor may be too ill to accomplish the gift, in which case a properly drafted power of attorney must be in place to authorize an agent to make the gift. It should also be kept in mind that it may also take several days to effectuate the transfer of bank or investment account assets, raising the risk that the donor may die before the transfers can be completed.

Before any gifts are made, the effect of the loss of the income tax basis adjustment at death should be taken into account. The tax basis of a gifted asset “carries over” from the donor to the donee, exposing the donee to income tax on the gain when they sell the asset. For example, assume that a taxpayer owns publicly-traded stock worth $1 million that would be exposed to Vermont estate tax at an 11% rate, and the stock has an adjusted income tax basis of $100,000. If the taxpayer owns the stock at death, and it is subsequently sold at a time when there has been no post-mortem appreciation in value, no state or federal income tax would be due, and the Vermont estate tax would be $110,000. On the other hand, if the taxpayer made a gift of the stock to his children before death, and the asset is subsequently sold, the Vermont and federal income tax liability could be as much as $240,000.[30] If there is no plan to sell the stock in the foreseeable future at the time of the gift, then time value of money considerations will also have to be taken into account.

Vermont Estate Tax Planning for non-Vermont Residents

While nearly all of the considerations discussed above will apply to non-Vermont residents, a few comments specifically directed to their situations are appropriate. The first observation to make is that in the majority of cases the property includible in the “Vermont estate” will be a second home, or perhaps a parcel of land or commercial or residential rental real estate, with a situs in Vermont. It should be noted, though, that the Vermont estate tax also reaches tangible personal property (a boat, vehicles, airplane, etc.) if such property is located in Vermont at the time of the non-resident owner’s death.[31]

Gifting

It should be apparent that, in the absence of a Vermont gift tax, non-residents should give particular attention to the possibility of making gifts of their Vermont assets prior to their deaths, and/or moving any valuable tangible personal property out of the state prior to death. In second home situations, it may be appropriate to consider a qualified personal residence trust (“QPRT”), if the owners want to retain use and enjoyment of the property for a period of time. Creation of a QPRT will result in a completed gift of the remainder interest in the property,[32] typically to the children, and will therefore be out of the Vermont transfer tax system.

Acquisition and Titling of Vermont Assets

In some cases, the manner in which an interest in Vermont property is acquired or held could be critical with respect to the application of the Vermont estate tax. This is because the “Vermont gross estate” of a nonresident is defined to specifically exclude “the value of intangible personal property owned by the decedent.”[33] Technically, this definition not only excludes publicly-traded securities, but partnership interests, LLC membership interests, and stockholdings in entities that own Vermont property. This raises the obvious question of whether a nonresident could transfer a Vermont second home to an LLC, then transfer interests in the LLC to their children while retaining a membership interest for themselves, and thereby avoid the Vermont estate tax. While the authors could find no authority addressing this issue in Vermont, it seems possible, if not likely, that the Vermont Department of Taxes would take the position that the LLC membership interests of a nonresident decedent must be included in their Vermont gross estate in such instances. In doing so, they might refer to legislative intent as expressed in an analogous situation involving the land gains tax, which treats transfers of “shares in a corporation or other entity, or of comparable rights or property interests in any other form of organization or legal entity, which effectively entitles the purchaser to the use or occupancy of land” as a transfer of the land itself.[34] While one could reasonably argue that legislative “intent” expressed with respect to one type of tax cannot be extended to another type of tax without express authority, how the Vermont Supreme Court might rule in such a case is unknown. Given the availability of other planning alternatives to nonresidents, particularly gifting techniques, it would not appear to be advisable to rely upon this method to avoid the Vermont estate tax.

A final point: nonresidents considering purchasing a second home in Vermont should consider the option of acquiring the property in the form of a “joint purchase,” whereby the parents acquire a life estate in the property, with the remainder being purchased by their children. If structured correctly, upon the deaths of the parents, the life estates will be extinguished, leaving nothing of value to be taxed in Vermont (or by the IRS). The specifics of this technique are beyond the scope of this article, but it could be useful, particularly where an expensive piece of real estate is involved.

Conclusion

As can be seen, planning for the Vermont estate tax is a complex exercise, requiring an analysis of the size of the potential estates, the asset mix, income tax basis, age of the taxpayer, potential changes in the federal estate/gift tax laws, gifting opportunities and risks, and other factors unique to the taxpayer’s personal situation. Needless to say “one size fits all” estate plans and formulas are not likely to achieve the goal of minimizing exposure to the Vermont estate tax, although as discussed above, there are a limited number of specific techniques that could be successfully employed in appropriate situations.

[1] $5 million, adjusted for inflation as of October 20, 2011. IR-2011-104.

[2] If the current federal estate tax laws are allowed to sunset, marginal estate tax rates on estates greater than $1 million begin at 41%.

[3] 32 VSA § 7442a. The Vermont estate tax return form and table of rates can be found at http://www.state.vt.us/tax/formsincome.shtml.

[4] Vermont law also provides for an “adjustment” to all taxable estates in the form of an automatic $60,000 deduction, which is inherent in the calculation of the pre-2001 federal state death tax credit that the Vermont law incorporates to determine the rate of Vermont’s estate tax. For purposes of this article, all examples used will assume this adjustment has been taken into account.

[5] The recently-enacted Miscellaneous Tax Bill of 2012 amends 32 VSA § 7475 to provide that the federal estate and gift tax laws as in effect on December 31, 2011 are adopted for purposes of calculating the hypothetical federal estate tax liability, thereby changing the applicable federal tax rate used for this purpose from 45% to 35%. Act 0143, Sec. 12.

[6] 32 VSA § 7475. In cases where no federal estate tax return is required to be filed, a “pro forma” federal estate tax return must be prepared and attached to the Vermont estate tax return; otherwise, the actual federal estate tax return is attached, but the hypothetical federal estate tax calculation is used. 32 VSA § 7445.

[7] 32 VSA § 7442a(c).

[8] Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C.) § 2010(c)

[9] The recent legislative adoption of federal estate and gift tax laws as in effect on December 31, 2011 “for the purpose of calculating the tax liability under this Chapter” [See 32 VSA § 7475, as amended by Act 0143, Sec. 12] raises the question of whether the hypothetical federal estate tax calculation can take into account the unused exemption of a predeceased spouse, provided the federal estate tax law requirements are otherwise met, including making the appropriate election on a timely filed federal estate tax return for the predeceased spouse. To the knowledge of the authors, the Vermont Department of Taxes has not yet taken a position on this issue.

[10] A note to non-professionals reading this article: while $2.7 million seems like and is a lot of money, it is very important to recognize that the taxable gross estate of a decedent includes life insurance policy proceeds as well as other tangible and intangible assets. Often, a person can be unaware that they have a potentially taxable estate after taking into account life insurance policies and the value of real estate, as well as investments.

[11] 32 VSA § 7401(a) (which also extends such “married” treatment to civil union couples).

[12] I.R.C. § 2056(b)(7); Treas. Reg. § 20.2056(b)-7(b)(2).

[13] By requiring all income to be paid to the surviving spouse not less often than annually, and with no person having the power during the surviving spouse’s lifetime to appoint the assets to anyone other than the surviving spouse. I.R.C. § 2056(b)(7)(B)(ii).

[14] 32 VSA 7475.

[15] 3 VSA §808 requires each agency to issue declaratory rulings upon petition.

[16] § 901, P.L. 107-16 (as amended).

[17] This is an approximation. The top Vermont marginal income tax rate is 8.95%, which would apply to most of the gain in this example. For most categories of property, including personal residences and investments, there is no capital gains exclusion or favorable tax rate in Vermont, although the federal exclusion for gains from the sale of a principal residence also applies for Vermont tax purposes. In general, for Vermont purposes, a 40% capital gains exclusion applies to gains from sales of certain depreciable property and from the sale of real estate other than a personal residence. 32 VSA § 5811(21)(B)(ii). This example assumes the entire gain is attributable to the sale of assets that do not qualify for the 40% Vermont capital gains exclusion, and that do qualify for the federal capital gains rate of 15%, resulting in a combined federal/Vermont rate of roughly 24%.

[18] In most cases, all of Molly’s assets, held outside of the bypass trust, will qualify for the income tax basis adjustment to fair market value upon her death; hence, there will be little or no taxable gain if they are sold shortly thereafter.

[19] Under the facts here, if the bypass trust were funded with assets less than $2 million, the surviving spouse’s estate would begin to be exposed to federal estate tax upon the spouse’s death since it would exceed $5 million. Thus, at certain levels there is a “trade-off” between estate tax and income tax benefits. With federal estate tax rates at 35% and capital gains rates at 15%, the situation favors taking steps to minimize the estate tax at the expense of losing the basis step-up, but the current volatility in our federal tax laws means that planners need to be alert to changes that would alter this calculus.

[20] Gain of $2.2 million; assumes asset appreciation is shared proportionally among all of the couple’s assets.

[21] In this case, there would also be federal estate tax due since the taxable estate plus prior gifts is greater than $5,120,000.

[22] The estate tax on the remaining $7,250,000 estate would be $689,360, whereas the tax on an estate of $10,000,000 would have been $1,076,720.

[23] I.R.C. § 2503(b) ($10,000 exclusion, adjusted for inflation).

[24] 32 VSA 7442a(c), referencing I.R.C. § 2001. The federal estate tax is imposed on the “taxable estate” plus “adjusted taxable gifts.” I.R.C. § 2001(b). Therefore, only “taxable gifts” have the effect of using the federal exemption.

[25] I.R.C. § 2503(e).

[26] $13,000 x 5 = $65,000; x 3 years = $195,000;. + $80,000 = $275,000.

[27] 32 VSA § 7442a(a) provides: “A tax is hereby imposed on the transfer of the Vermont estate of every decedent … ” (italics added). The related definitions of Vermont “gross estate” and “taxable estate” refer to the federal gross and taxable estates of decedents, terms which under federal law do not include prior taxable gifts. 32 VSA § 7402 (13) & (14). See I.R.C. §§ 2001, 2031, 2051.

[28] 36 MRS § 4102 1.

[29] See Burnet v. Guggenheim, 288 U.S. 280 (1933).

[30] See supra note 13.

[31] 32 VSA § 7402 (13).

[32] I.R.C. § 2702(a)(3).

[33] 32 VSA § 7402 (13).

[34] 32 VSA § 10004(c).

Back to Articles listings page